Any comments, contributions, or feedback? Ping me!

Follow @adlrocha Tweet to @adlrocha

@adlrocha - Traversing the NAT

A quest for direct global connectivity between devices.

These past few weeks I’ve been pretty obsessed with the future of the Internet, how it may look like, and the technological path towards it. All this started when I jumped into writing my personal vision for a new Internet. A few weeks later I was invited to participate in a discussion panel about the future of the Internet and web3 in the European Blockchain Convention, and as preparation for the panel I decided to interview a bunch of colleagues in the field to learn their thoughts on the matter. I concluded this series with last week’s discussion on local-first software and the technologies to enable it.

A recurring challenge that has appeared in the aforementioned pieces around the construction of a new Internet is the need for global connectivity. To achieve global and direct connectivity between devices one of the big challenges we need to solve efficiently is NAT traversal. In this publication we will explore the problem of NAT traversal from current solutions, to decentralized alternatives and some ideas for the future.

Stating the problem

So why are NATs (Network Address Translators) a problem for global direct connectivity between devices? Network address translation is a mechanism used to remap from an IP address space into another by modifying the network address information of IP header packets while in transit across traffic routing devices.

Why would we want to do this? Well, the Internet was originally designed in such a way that every connected device was meant to have its own unique IP. This meant a different public IP address for each of your connected devices at home. IP addresses are a finite resource (the 32 bits of IPv4 allows roughly 4.2 billion IP addresses), so before IPv6 (where IP scarcity has been virtually removed by having 128 bits addresses), we needed a way to prevent every connected device from requiring a public IP.

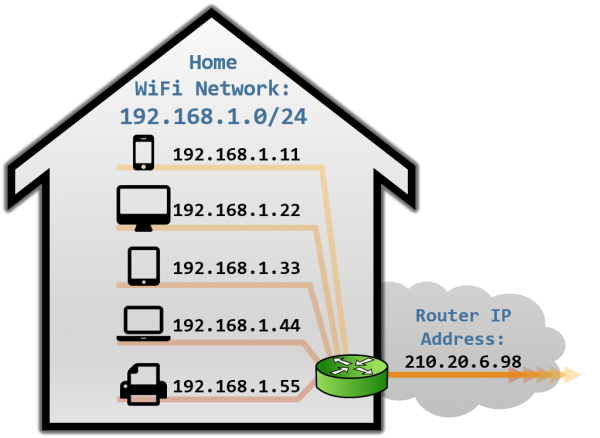

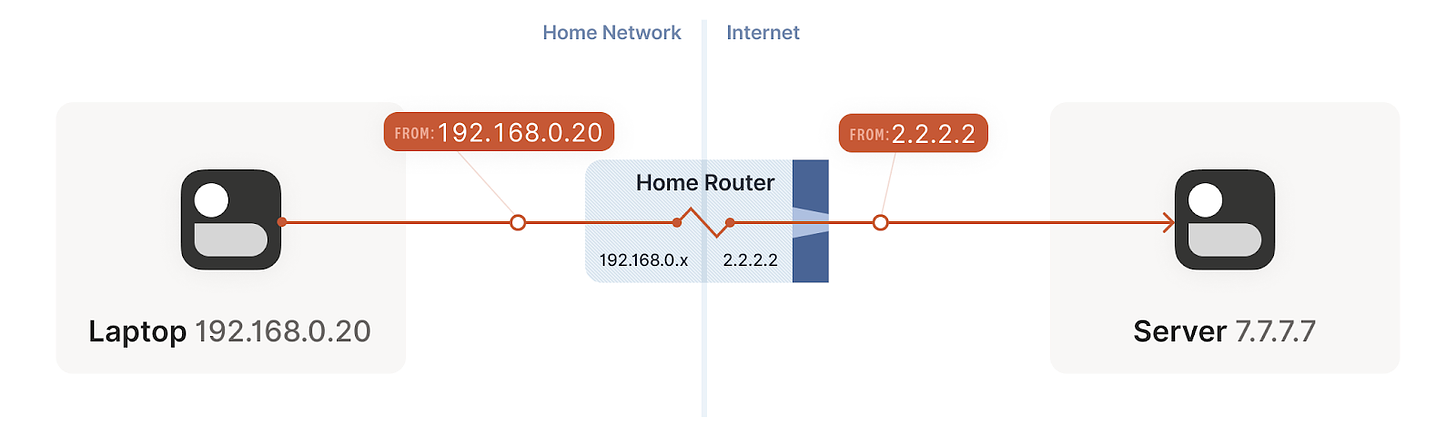

Thus, in RFC 1918 three different address sets were considered free to use and reuse by organizations: 10.0.0.0/8, 172.16.0.0/12, 192.168.0.0/16. These addresses were labeled as Private addresses, and were deemed non-routable on the Internet. All the remaining addresses remained Public addresses, and hence routable from anywhere in the Internet. All of this led to the scenario we have currently at home, where our ISP assigns a public IP to our router, but our devices are assigned a private IP from our own private subnetwork. Our devices don’t have a public address directly dialable from the Internet.

With this setup in place, we can start connections from our local devices (with private IP addresses) to public IP addresses on the Internet. Our router gets our packets, translates our private IP address to the corresponding public IP address, and starts a new connection from one of its ports to the target IP. The router then stores a tuple (private IP, port) so he knows how to map responses coming to that specific port to the local device that established it.

So dialing the Internet from our local device with a private IP is easy, but what about the other way around? What if I have a local server at home hosting a web application that I want to make accessible from the public Internet? There is no straightforward way of achieving this. We can “teach” our router with a rule such that “every request entering this specific port through the public interface should be redirected to this port in this private IP”. This would work as long as our public IPs were static (which is generally not the case). Even more, for all of these examples we are considering just one of the devices behind a NAT, but things get even messier when the two of them are behind a NAT, how can we establish a connection then if we don’t even know what IP to dial?

In short, because of NATs and IP addresses being a limited resource we don’t have a scalable way of having direct connectivity between devices.

Learning from WebRTC

The fact that in the current Internet we don’t have an easy way of establishing a direct connection between two devices behind NATs is not only messing with future applications to come, it already bugs widespread P2P protocols such as WebRTC. Fortunately, NAT traversal has been studied for decades, and WebRTC already uses a good bag of tricks to send peer-to-peer audio, video and data between web browsers, helping us in our quest to global direct connectivity at scale.

The first thing you learn when you start exploring the design of “NAT-friendly protocols” is that they should be based on UDP. You can do NAT traversal with TCP, but it adds another layer of complexity to an already quite complex problem, and may even require kernel customization depending on how deep you want to go. But say you want to use TCP because you need a stream-oriented reliable connection? No problem, that is one of the reasons why QUIC was invented (remember QUIC?), and fortunately, QUIC runs over UDP.

So with this in mind, what do we need to use to allow our UDP traffic traverse the obstacles of the Internet?

A friendlier obstacle: stateful firewalls

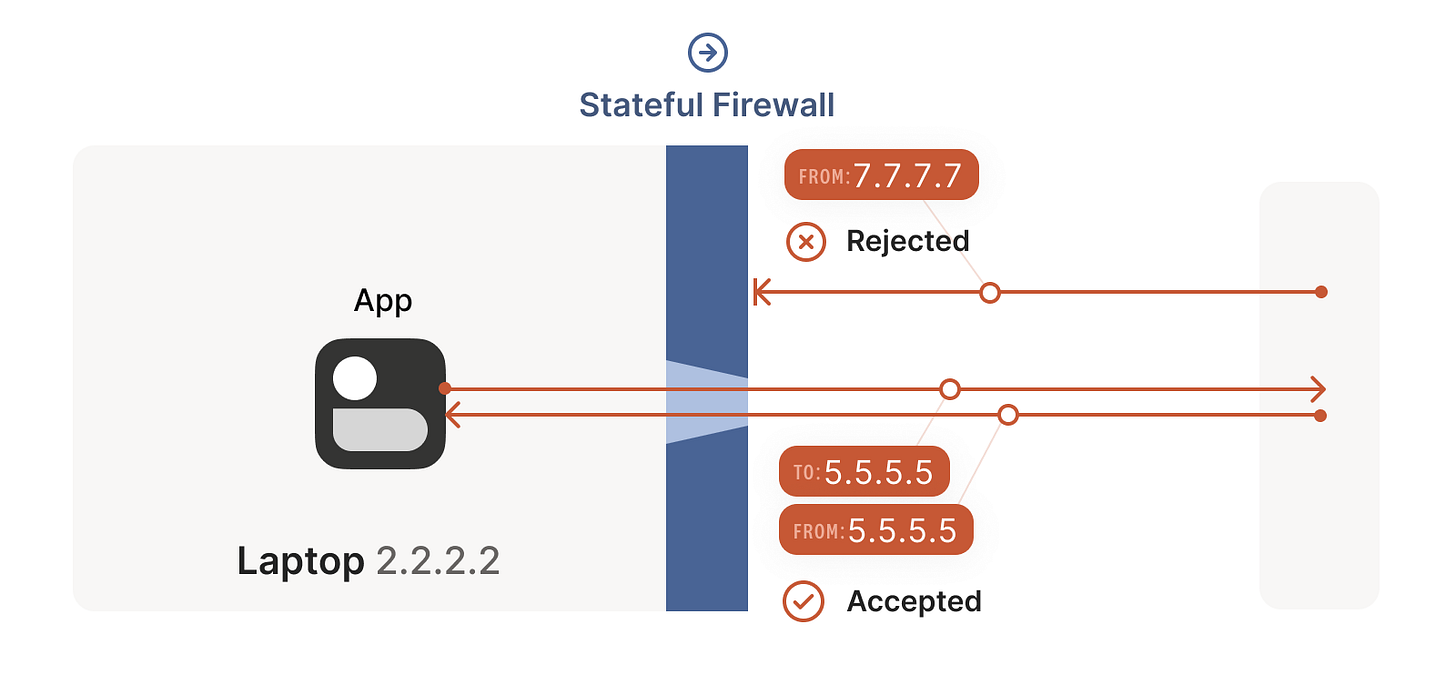

A good way of evaluating ways of solving NAT traversal is to get inspiration from firewalls. Stateful firewalls remember what packets they’ve seen in the past and can use that knowledge when deciding what to do with new packets that show up. Examples of these types of firewalls are Ubuntu’s ufw (iptables/nftables for my beloved Linux nerds), BSD’s pf in MacOS, or AWS security groups. Let’s illustrate these types of firewalls with an example from here.

Source: https://tailscale.com/blog/how-nat-traversal-works/

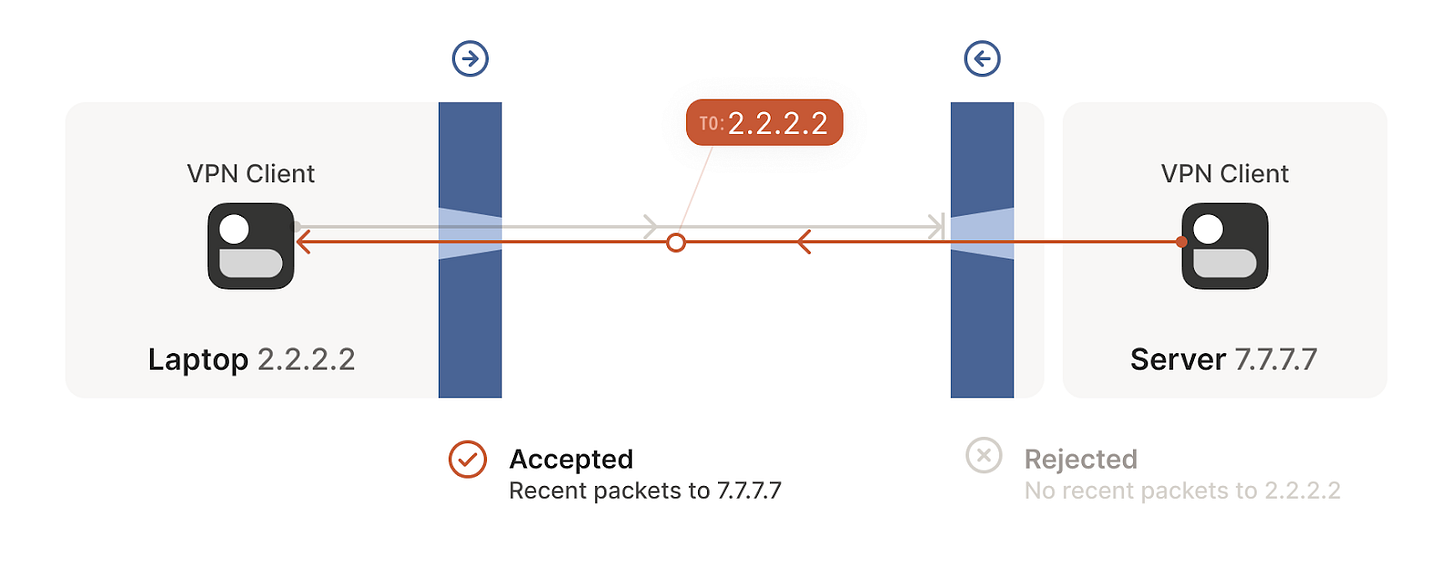

For UDP, the rule is very simple: the firewall allows an inbound UDP packet if it previously saw a matching outbound packet. For example, if our laptop firewall sees a UDP packet leaving the laptop from 2.2.2.2:1234 to 7.7.7.7:5678, it’ll make a note that incoming packets from 7.7.7.7:5678 to 2.2.2.2:1234 are also fine. The trusted side of the world clearly intended to communicate with 7.7.7.7:5678, so we should let them talk back.

As already mentioned above for the case of NATs, in a client-server setup, where the client is the one that sits behind a NAT or a firewall, this is not that big of a deal, because clients are usually the ones that start new connections, so whenever the firewall detects the outbound connection establishment, the server will be able to answer back the client. The problem arises when both devices are behind firewalls, a common setup with p2p applications and protocols.

Circumventing firewalls is not that hard. As it was also briefly mentioned, we can configure them to accept connections from specific IP, so a connection can be established from the outside and there is no need to start the connection establishment from behind the firewall.

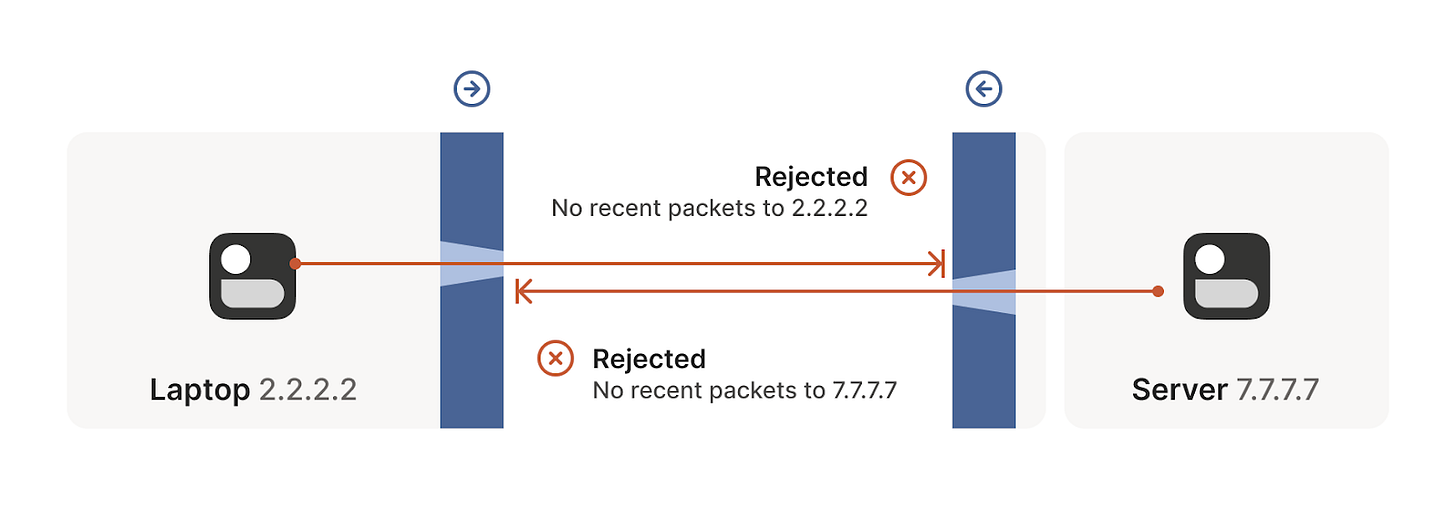

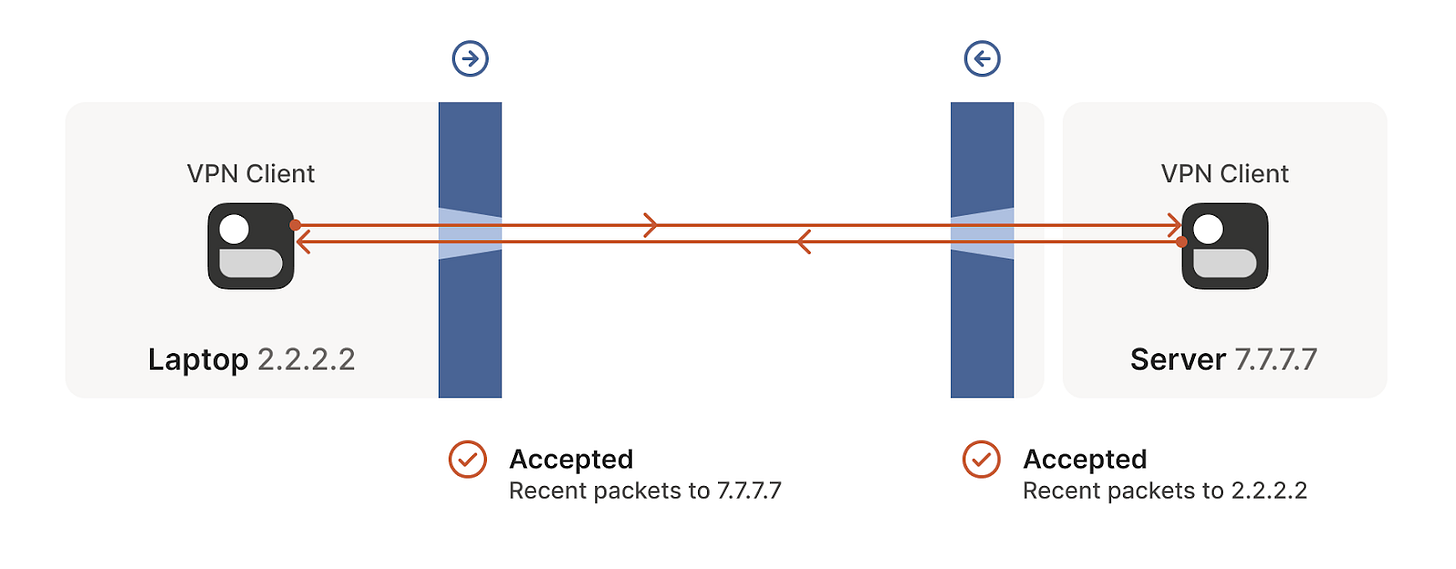

But we can even circumvent stateful firewalls without having to explicitly configure it. If we have two devices behind their corresponding firewalls, they can both try to start a new connection from inside at the same so that even if their first attempt is rejected, as the other device is also trying to start the same connection from inside, it will succeed in the next attempt (see the following figures). This simple principle will be of great use to solve our NAT traversing problem.

- Connection establishment rejected in one direction

- Connection establishment rejected in the other direction.

- The tunnel is opened in the next attempt

The real obstacle, NATs.

We can think of NAT (Network Address Translator) devices as stateful firewalls with one more really annoying feature: in addition to all the stateful firewalling stuff, they also alter packets as they go through. There are several types of NAT, but when talking about connectivity problems and NAT traversal, all the problems come from Source NAT, or SNAT for short. As you might expect, there is also DNAT (Destination NAT), and it’s very useful but not relevant to NAT traversal.

As introduced above, the most common use of SNAT is to connect many devices to the internet, using fewer IP addresses than the number of devices.

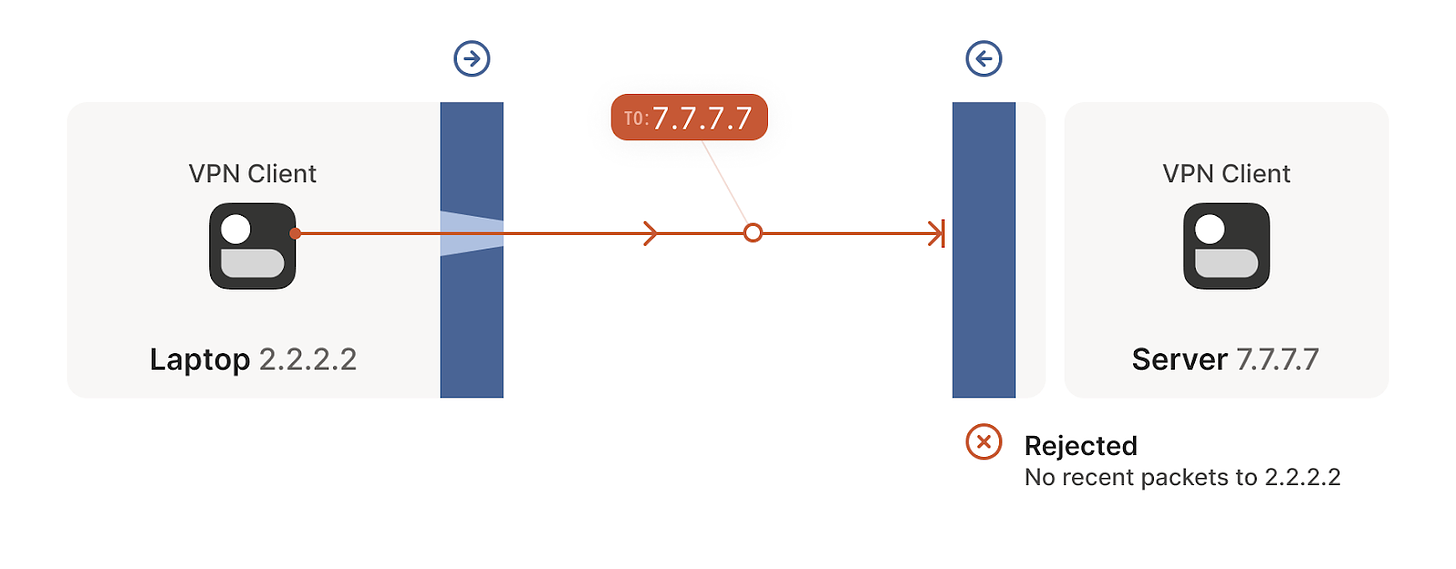

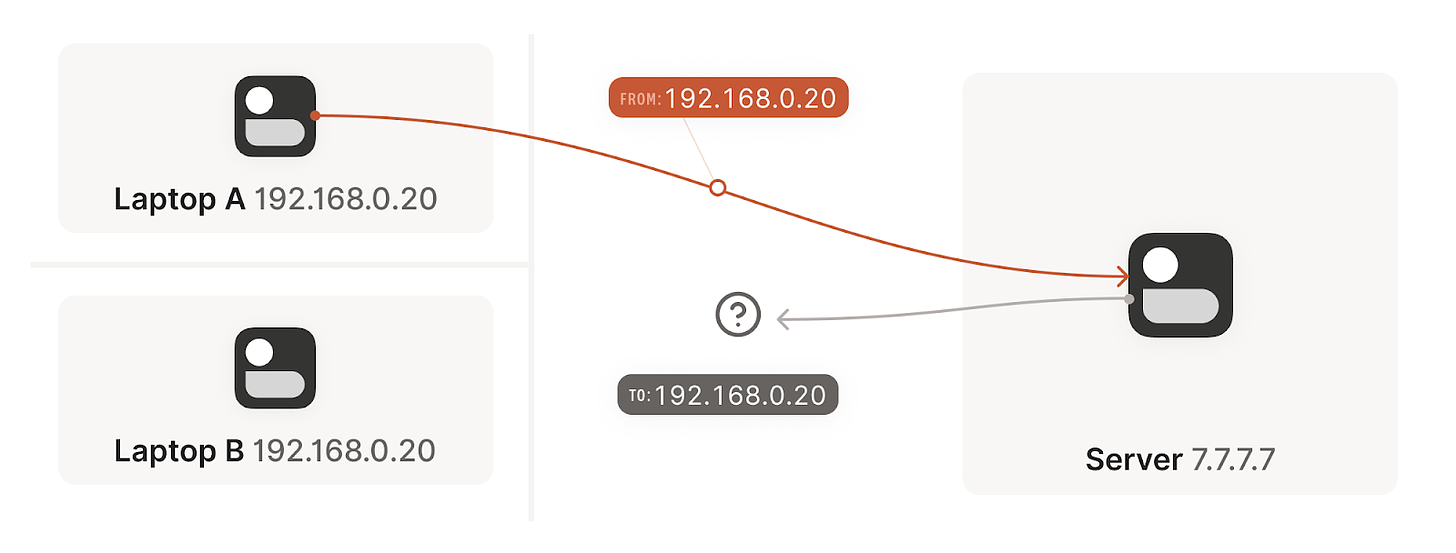

Remember from our example above (illustrated here), that when we establish a new connection to the Internet, our home router maps the outbound connection with a specific port, so that when traffic arrives to that port it knows how to translate the IP, and to what device and port in the local network to send it. This is great when we are dialing a public IP address, but we achieve a deadlock when both devices are behind a NAT, how can we establish a new connection to know the port of the IP address to which to send the traffic. Even more, what is the public IP address I need to dial in the first place?

STUN

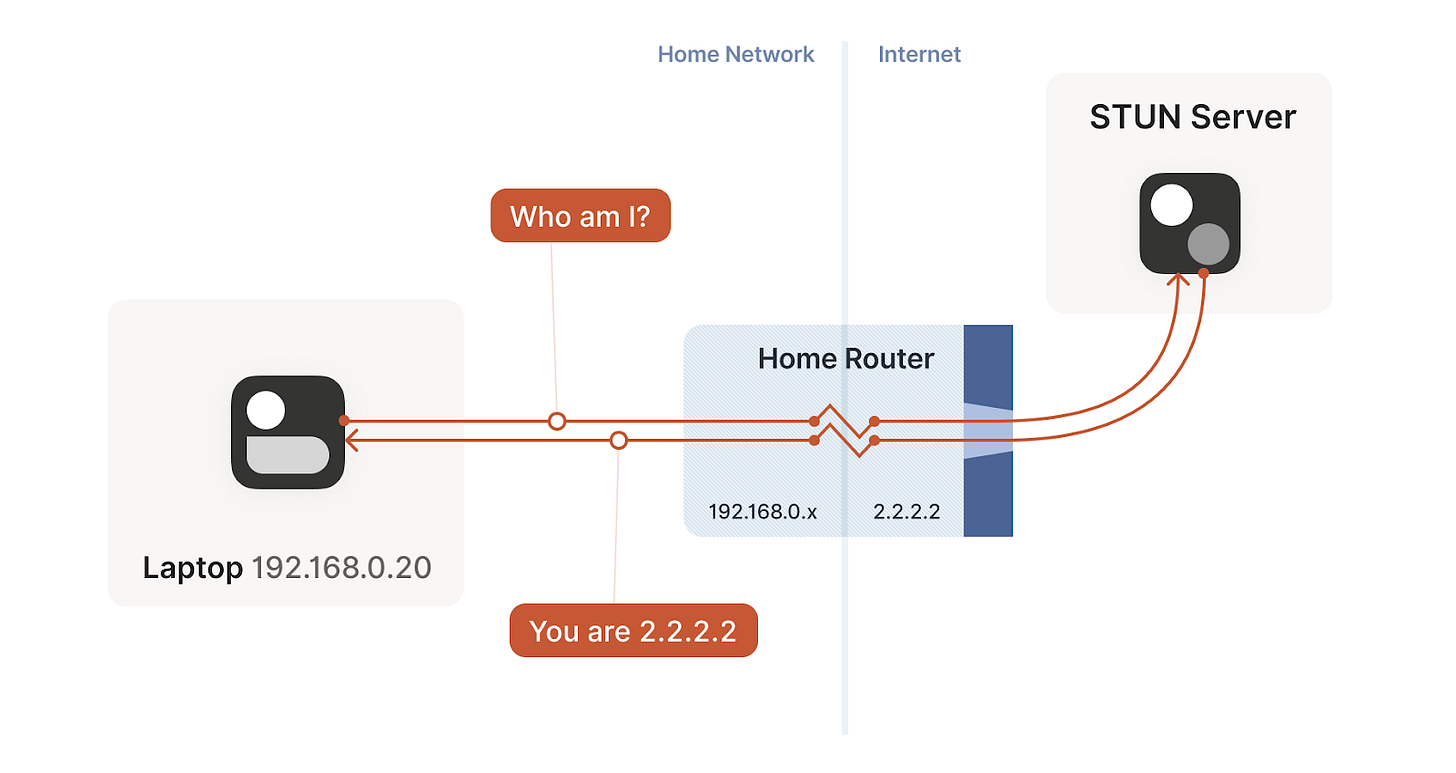

One of the techniques introduced by WebRTC to solve this paradox is through STUN. STUN is both a set of studies of the detailed behavior of NAT devices, and a protocol that aids in NAT traversal**. STUN relies on a simple observation: when you talk to a server on the internet from a NATed client, the server sees the public ip:port that your NAT device created for you**. So, the server can tell you what ip:port it saw. That way, you know what traffic from your LAN ip:port looks like on the internet, you can tell your peers about that mapping, and now they know where to send packets!

That’s fundamentally all that the STUN protocol is: your machine sends a “what’s my endpoint from your point of view?" request to a STUN server, and the server replies with “here’s the ip:port that I saw your UDP packet coming from."

Unfortunately, this doesn’t work with every NAT. The problem is an assumption we made earlier: when the STUN server told us that we’re 2.2.2.2:4242 from its perspective, we assumed that meant that we’re 2.2.2.2:4242 from the entire internet’s perspective, and that therefore anyone can reach us by talking to 2.2.2.2:4242.

As it turns out, that’s not always true. Some NAT devices behave exactly in line with our assumptions. Their stateful firewall component still wants to see packets flowing in the right order, but we can reliably figure out the correct ip:port to give to our peer and do our simultaneous transmission trick to get through. Those NATs are great, and our combination of STUN and the simultaneous packet sending will work fine with those.

Other NAT devices are more difficult, and create a completely different NAT mapping for every different destination that you talk to. On such a device, if we use the same socket to send to 5.5.5.5:1234 and 7.7.7.7:2345, we’ll end up with two different ports on 2.2.2.2, one for each destination. If you use the wrong port to talk back, you don’t get through.

TURN

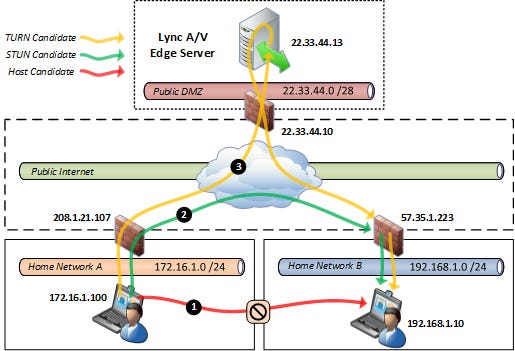

Traversal Using Relays around NAT (TURN) is another protocol that can be used to circumvent the effect of NATs in the Internet. If a host is located behind a NAT, then in certain situations it can be impossible for that host to communicate directly with other hosts. In these situations, it is necessary for the host to use the services of an intermediate node that acts as a communication relay. TURN is generally used when STUN has failed.

First, the client contacts a TURN server to request relaying resources. If the TURN server accepts the device’s request, it responds to the device with the control information required to perform a connection using the TURN server as relay. The TURN server receives the data from the client and relays it to the peer using UDP, which contain as their Source Address the “Allocated Relayed Transport Address”. The peer receives the data and responds, again using a UDP datagram as the transport protocol, sending the UDP datagram to the relay address at the TURN server. The TURN server receives the peer UDP datagram, checks the permissions and if they are valid, forwards it to the client.

Scaling for the future

All of the NAT traversal techniques presented above require, to a greater or lesser extent, from third-parties or centralized infrastructures to work. And we all know that centralized systems and third-parties can become a bottleneck for scale, security and privacy. To get a grasp of what is being done in the decentralized space to prevent this, let’s have a look at some of the NAT traversal protocols proposed by the folks at libp2p.

All of them are decentralized alternatives to the traditional NAT traversal protocols mentioned above:

-

Hole-punching (STUN): One of libp2p’s core protocols is the identify protocol, which allows one peer to ask another for some identifying information. When sending over their public key and some other useful information, the peer being identified includes the set of addresses that it has observed for the peer asking the question. This external discovery mechanism serves the same role as STUN, but without the need for a set of “STUN servers”.

-

AutoNAT: While the identify protocol described above lets peers inform each other about their observed network addresses, not all networks will allow incoming connections on the same port used for dialing out. Once again, other peers can help us observe our situation, this time by attempting to dial us at our observed addresses. If this succeeds, we can rely on other peers being able to dial us as well and we can start advertising our listen address.

-

Circuit Relay (TURN): Circuit relay is a transport protocol that routes traffic between two peers over a third-party “relay” peer (similar to what TURN does).

You may see that for now all of these proposals are focused on removing the reliance on centralized infrastructures to achieve NAT traversal. Unfortunately**, you still need to trust a third-party for this to work** (the node you are requesting your information from, a realy, etc.). It would be great if when you “ask a traversing favor” to other peers you can be sure that you would be treated fairly, and that your traffic will be forwarded as planned.

But hey! We have cryptography, we have blockchains, we have consensus algorithms. Why not use all of them to build as part of the new Internet an incentivized system to help with NAT traversal? The same way we rent storage and we can be sure that our data is stored (the Filecoin-way), we can rent forwarding capabilities to perform NAT traversal and traffic relay in a reliable way. I already came across a paper that explores (in my opinion quite shallowly) the idea of rewarding relays for decentralized NAT traversal.

So these decentralized alternatives for NAT traversal can end up becoming the foundation for a bigger piece of the new Internet yet to come (the same way IPFS built the foundations for Filecoin). In any case, NAT traversal as-is already is an extremely exciting topic, so if you want to dive even deeper into the field check out this article, and this book. See you next week!

Any comments, contributions, or feedback? Ping me!